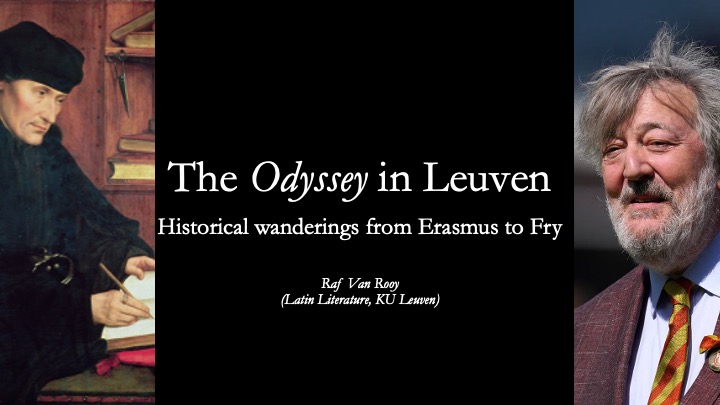

The Odyssey in Leuven:

Historical wanderings from Erasmus to Fry

Introduction to the interview of

Sir Stephen Fry

by Thomas Vanderveken

(Saturday 29 March 2025, Grote Aula, Maria-Theresiacollege)

at the occasion of

his honorary doctorate on Friday 28 March 2025

(promotores: Liesbet Heyvaert, Geert Brône, and Geert Roskam)

To celebrate both the honorary doctorate Sir Stephen Fry received from KU Leuven and his recent retelling of Homer’s Odyssey (2024), I would like to take you on a historical journey. This will be an opportunity to showcase the history of the Odyssey in Leuven on a few stops, thereby sharing our local research into the text’s vicissitudes, about as multifarious as that of the title hero himself. It is a history of reading, teaching, studying, and imitating the great poem by Homer in and around Leuven.

1. Erasmus in and around Leuven

Our first stop is the inimitable Erasmus of Rotterdam (ca. 1469–1536), who brought Greek language and literature back to Leuven, drawing on the work of Italian humanists and Greek migrant scholars. As part of this endeavour, Erasmus engaged with the Odyssey in Leuven during the early sixteenth century. But before turning to Leuven, imagine you are in Brussels, on 6 January 1504. An early-career Erasmus is standing on the podium, probably as nervous as I am now, in the presence of greatness. Erasmus was nervous because he was about to sing the praise of Philip the Handsome (1478–1506). This prominent Habsburg prince had just arrived back home from a trip to Spain. Erasmus’s praise was evidently written and recited in Latin, the principal language of culture at the time, but for this formal occasion Erasmus presumably also composed the following short poem in Greek:

Illustrissimo principi Philippo reduci Homerocenton

Χαῖρε Φίλιππε, πάτρας γλυκερὸν φάος, ὄρχαμε λαῶν.

Ὦ φίλ’, ἐπεὶ νόστησας ἐελδομένοισι μάλ’ ἡμῖν

σῶός τ’ ἠύς τε μέγας τε, θεοὶ δέ σε ἤγαγον αὐτοί,

οὖλέ τε καὶ μάλα χαῖρε, θεοὶ δέ τοι ὄλβια δοῖεν

καὶ παισὶν παίδων καὶ τοὶ μετόπισθε γένωνται.

Ἄλκιμος ἔσσ’ αἰεί, καὶ σοῦ κλέος οὐκ ἀπολεῖται.

A Homeric cento to the most illustrious Prince Philip, upon his return

Welcome Philip, sweet light of the fatherland, leader of nations.

Dear prince, now that you have returned to us, who desired it so much,

safe and sound, and brave, and great, and the gods have guided you themselves,

health and great joy be with you, and may the gods grant prosperity to you

and to your children’s children and to those who will be born afterwards.

Always be brave, and your fame will not perish.

(Text and translation from Lamers – Van Rooy 2022, 223–24)

Perhaps Erasmus recited this Homeric cento, too: six lines put together out of words and (half)verses from Homer’s Odyssey. The Homeric theme was of course very suitable for celebrating the nostos of a prince after a long journey. Philip the Handsome was the new Odysseus, and Brussels the new Ithaca. As such, Erasmus’s choice of topic and language was well-considered, as well as very original, since the cento formed an early composition in so-called New Ancient Greek – a language imitating the literary dialects of ancient Greece and used by scholars since the Renaissance.

I have read the Greek using modern pronunciation, not to please Cavafy and the modern Greeks, to whom Fry’s Odyssey is dedicated, but because Erasmus and most of his early sixteenth-century colleagues pronounced it that way. This so-called vernacular (or Reuchlinian) pronunciation caused severe difficulties in teaching, as we will see in our historical journey from Erasmus of Rotterdam to Sir Stephen Fry, fortunately for everyone involved here much shorter than Odysseus’s own mythical adventure of ten years. But what is the link of this episode with Leuven? The Homeric cento was recited in Brussels and first published in Antwerp in 1504 in a rather ugly Greek font (Figure 1).

(courtesy of Ghent, Ghent University Library, Book Tower, BHSL.RES.0149/2)

The clue lies in how Erasmus studied Greek: he taught the language and literature of ancient Greece to himself, first in Paris and Orléans (where he was hiding from the plague), finishing off here in Leuven. In this city, he spent much time with Homer’s two epic poems and other Greek literature. As an autodidact, Erasmus became one of the first – if not the first – to translate a full Greek tragedy into Latin, which also happened here in Leuven. The tragedy he chose to Latinize was likewise set in the Homeric world: Euripides’s Hecuba, which revolves around the wife of King Priam of Troy and mother of Trojan hero Hector. In sum, Erasmus disclosed the Greek classics to a new audience, using both the original Greek language in his cento and his beloved Latin in his translation.

Now this sounds rather familiar, doesn’t it? Indeed, I would like to argue that Erasmus was the Renaissance Fry, since they have a lot in common, in addition to a strong intellectual radiance (Figure 2).

Most notably, as of this week, like Fry, Erasmus had a strong connection to the universities of Cambridge and Leuven. Erasmus taught Greek at the former and instituted a Trilingual College at the latter (to which I will return). Like Fry, Erasmus was fond of Greek mythology and literature. He popularised the Greek classics, excerpting and translating many Greek texts including Homer’ Odyssey in his Adagia, a storehouse of classical proverbs. Like Fry, Erasmus was a defender of humanity, advocating for peace and tolerance. For instance, the Rotterdam humanist argued against a war with the Ottoman Turks. And above all, like Fry, Erasmus was a great narrator, communicator, and thus educator. He started advocating female education when he saw the fruits of it in his friend Thomas More’s daughters, contrary to the communis opinio.

There is, however, a major difference between Erasmus and Stephen Fry (other than priesthood!). Erasmus was never awarded an honorary doctorate from our institute and was rehabilitated here only in the last century, especially since the 1970s – think of the brutalist Erasmushuis housing the Faculty of Arts and his statuette close to the Fish Market (at the corner of the Mechelsestraat and the Schrijnmakersstraat, on the small Mathieu de Layensplein, where Erasmus tends to be blocked by phalanxes of bikes, not inappropriate for a Dutchman). Yet, I’m happy to see that our institute has now become more open to give an appropriate place of honour to talented persons that greatly contribute to the promotion of good letters and to a more open society.

2. The Collegium Trilingue Lovaniense

Our next stop is the Collegium Trilingue Lovaniense or the Three-Language College in Leuven (Figure 3), founded in 1517 under the will of Jerome of Busleyden (ca. 1470–1517), although the idea was de facto Erasmus’s. In essence, the college constituted a language institute where one could study – for free – the three so-called sacred languages Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. The underlying idea was twofold. On the one hand, the college’s professors taught the litterae humaniores, good literature that helped its readers reach the full potential of humankind and thus become humanior (‘more human’) – hence humaniora and the humanities. On the other hand, the college stimulated cross-cultural curiosity as well as critical reading and thinking. The likes of Andreas Vesalius and Gerardus Mercator adopted and advocated this approach in such different scientific disciplines as anatomy and geography. They cultivated doubts and made progress in doing so – a crucial skill emphasised by Fry in his acceptance speech yesterday.

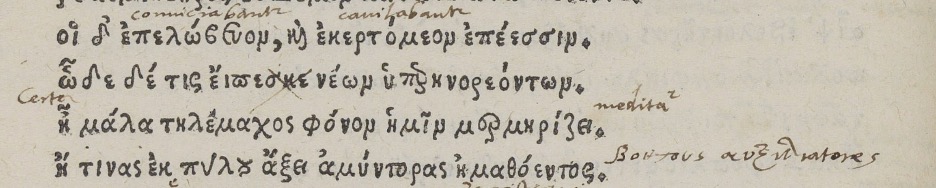

At the Trilingual College, Homer’s Odyssey was a favourite reading of Rutgerus Rescius (ca. 1495–1545), the first official public professor of Greek in the Low Countries, who originated from Maaseik in Limburg. Together with his colleagues at the Trilingue, Rescius opened up the great classics to a broader audience. The Greek professor continued the chain, initiated by Erasmus, of reading and retelling the Odyssey in the Low Countries that persists to this very day. We are fortunate enough to have student notes from the Trilingual College which show the enormous effort one had to invest in studying Homer’s difficult Greek five centuries ago. These notes can now be explored by anyone interested through our Database of the Leuven Trilingue, DaLeT in short (www.dalet.be). I will focus for now on one experience of a student listening to Rescius’s lectures on Odyssey 2.323–26 and annotating his textbook during the fall of 1543 (Figure 4).

In this passage, a young suitor mocks Telemachus for planning to seek his wandering father. “He is actually planning to get help for murdering the suitors,” the youngster jokes – ironically, as we know they all get killed at the end of the story. In A. T. Murray’s early twentieth-century translation, this passage reads:

They mocked and jeered at him in their talk; and thus would one of the proud youths speak: “Aye, verily Telemachus is planning our murder. He will bring men to aid him from sandy Pylos.” (Murray 1946 [1919], I, 59–61)

The phrase “to aid him” translates the Greek ἀμύντορας (pronounced “amindoras”), which the professor Rescius glossed as βοηθοὺς auxiliatores (pronounced “voitous auxiliatores”), so first in Greek, then in Latin. Yet, the student only realized halfway through that the professor had changed language, so the first part of the Latin word auxiliatores is still in the Greek alphabet! (See Figure 4 and DaLeT Annotation ID 1136.)

The student was of course confronted with various hurdles. For instance, the professor had no blackboard to write on (even though it was already in use for musical education). In combination with the difficult pronunciation of Greek, which did not reflect spelling at all, it was a disaster for students to learn Greek. A lot of learning went wrong, especially if the professor had the ambition of explaining Homer next to Latin also in Greek, both languages that were not native for the students!

Funnily enough, the student seems to have corrected Homer in the second line in Figure 4, but it only seems so. He was actually trying to tame Homer’s odd-looking Greek by conforming it to the Attic standards of Plato and Demosthenes.

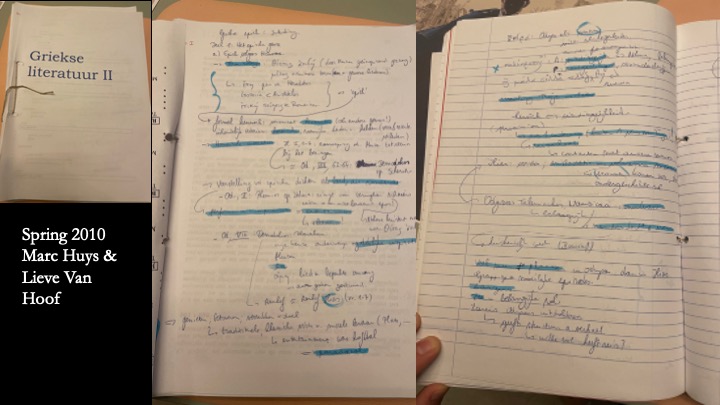

As a point of comparison, I can show my own student notes from the cherished classes with the late Professor Marc Huys and Professor Lieve van Hoof (Figure 5). These notes show improvements in teaching techniques vis-à-vis the sixteenth century: they were so kind as to use my native language as well as a blackboard, but the struggle with the Homeric text remains more or less the same, yet one that is worth the effort. In return for your trouble, you get a thesaurus of stories in a carefully crafted language that speaks to the ages.

Unlike Professors Huys and Van Hoof, the good Christians of the sixteenth century – the age of religious wars – had to justify their reading of pagan literature like Homer’s Odyssey. Fortunately, they found a justification in the Greek church father Basil the Great. According to professor Rescius, “the holy Basil the Great says that the entire oeuvre of Homer is nothing else but a praise of virtue. Therefore it should be read by Christians” (DaLeT Annotation ID 21). Today, the Odyssey is read differently, for its rich stories and for the human emotions that take centre stage in it. The blurb on the back cover of Fry’s retelling puts it eloquently: “A tale of love and longing, return and redemption, home and hope, Stephen Fry’s Odyssey weaves together the final threads of the tapestry begun in the worldwide bestseller Mythos. It is a story for the ages – and all ages.”

3. Homeric literature from Leuven and beyond

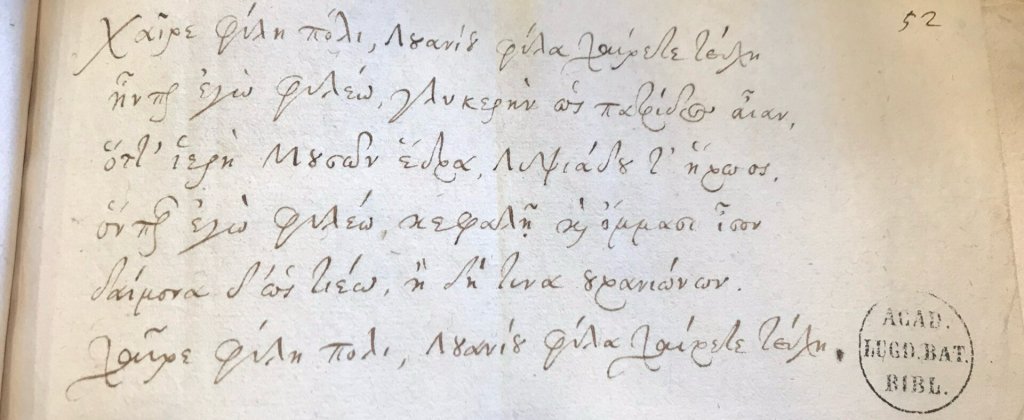

On the two final stops (which I promise to be much briefer!), I would like to explore the inspiration Homer’s Greek epic poems offered to writers in Leuven and beyond, who created a Homeric-style literature in the poet’s own language that continues up to this day. A charming example is this anonymous manuscript greeting of the city of Leuven, in which also a local hero is celebrated in dactylic hexameters (Figure 6). This hero did not earn his stripes in war, but in scholarship: Justus Lipsius, who like the Homeric heroes has a divine aura.

Χαῖρε φίλη πόλι, Λουανίου φίλα χαίρετε τείχη ἧνπερ ἐγὼ φιλέω, γλυκερὴν ὡς πατρίδος αἶαν, ὅττ᾿ ἱερὴ Μουσῶν ἕδρα, Λιψιάδου τ᾿ ἥρωος, ὅνπερ ἐγὼ φιλέω, κεφαλῇ καὶ ὄμμασι ἶσον δαίμονα δ᾿ ὡς τιέω, ἢ δή τινα οὐρανιώνων. Χαῖρε φίλη πόλι, Λουανίου φίλα χαίρετε τείχη.

I greet you, dear city, and dear city walls of Leuven! I carry you in my heart as my sweet fatherland, since you are the sacred seat of the Muses and the great Lipsius, whom I love as my head and as my own eyes and whom I revere as a god or one of the heavenly inhabitants. I greet you, dear city, and dear city walls of Leuven! (My translation)

The most impressive specimens of Homeric poems are, however, not from Leuven but from the present-day Netherlands. They are moreover inspired in the first place by the Iliad rather than the Odyssey, as can be expected in that age of eternal warfare (Eighty Years’ War), but they are too interesting to leave unmentioned. A sixteen-year-old schoolboy from Amersfoort composed an epic poem on the battle of Nieuwpoort, whereas a Dutch physician wrote an epic poem on the siege of Haarlem by the Spanish in 1572–73 (see Lamers – Van Rooy 2022; Lamers 2023).

4. Paulos Nikolaos, the Homer of Leuven

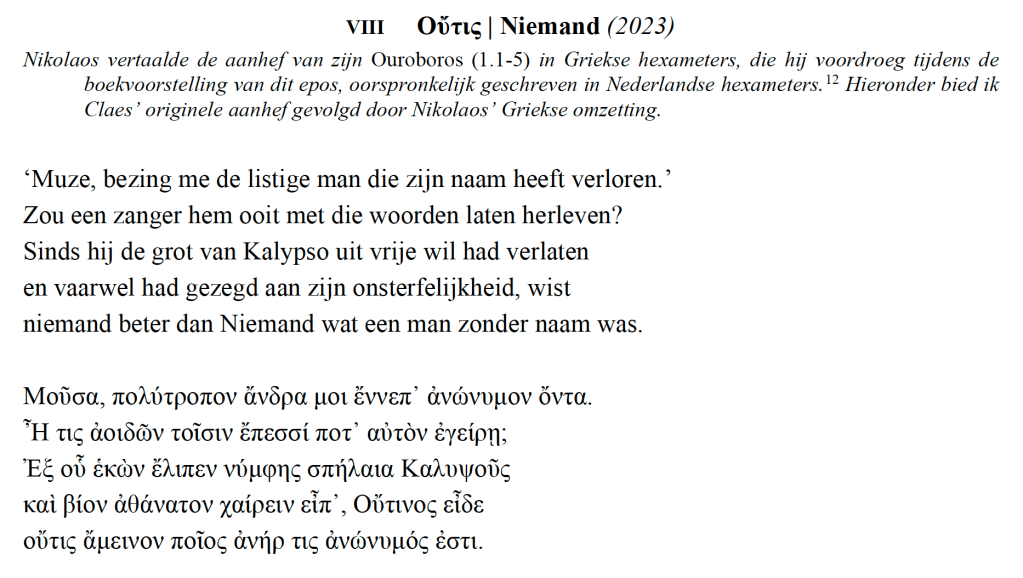

Back to Leuven for our final stop (Ithaca is calling!). Today, the city boasts a modern reincarnation of Homer, Paul Claes – or should I say Paulos Nikolaos? Claes is a literary jack-of-all-trades and, above all, an incredibly polyglot poet. For instance, in his 1983 De Zonen van de Zon (“The Sons of the Sun”), he varied the same sonnet in five modern languages (Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish), as well as in the two classical languages Latin and Greek, to tease out a theme from Greek mythology. Even more notably, one of his most recent publications, officially presented in October 2023 to celebrate his 80th birthday, is a Dutch sequel to the Odyssey. Like its exemplum, Claes’s Ouroboros: Odyssee 2.0 is written in hexameters, yet the Homer of Leuven has lent a cosmic aura to the story, with a very surprising ending in the last book (which I won’t give away – you’ll have to read it). Yet, Paul Claes would not be Paul Claes, if he had not done something even more special. He has provided a Greek version of the first lines of his Ouroboros (Figure 7)!

5. By way of conclusion: humanity’s Ithaca?

With the example of Paul Claes, the historical wanderings of the Odyssey in Leuven have come to an end – at least, for now. The epic poem continues to be read by students and laypeople in Leuven and around the world, whether in the original or in translations or other adaptations like the movie version that is currently being produced or – even better – Stephen Fry’s masterful retelling, which places the Odyssey in the broader context of the heroes’ nostoi.

In Leuven, we have had a long tradition of fascination with Homer’s Odyssey, arguably the longest in the entire Low Countries. It has been a tradition of reading, or rather struggling to read, the text in the original, taking inspiration from it to write new poetry, whether in Greek or in Dutch (not to mention other languages like Latin). That is the great thing about classics: as old as Greek and Latin literature may be, we can always do something new and fresh with them and use them to express messages that are extremely relevant to our own day and age. For Erasmus and the humanists, the relevance was that Homer praised Christian virtue avant la lettre. Fry draws other lessons for today – fortunately, I may add. One thing I take away from exploring Fry’s Odyssey in the past few weeks is the following remark, tucked away in a section titled “Further Adventures” at the very end of the book, but one of great momentum, as we experience a new period of crisis in humanity and – I am tempted to say – in human intelligence:

“In a world where absolute data and information are the vital currency – you might say, a world where absolute data and information are the gods – we do well, I am convinced, to remember the power of the non-absolute, the power of story, myth, ceremony, ritual and symbol. I see myself appearing a thousand times in the Greek myths – as a fool, bungler, criminal, lover, villain and – very rarely – hero. I have never recognized myself in ones and zeroes and digital data sets, like some lost Tron warrior sucked into the circuit, battling the pulses of current. While it’s very hard to believe or make sense of fact, fiction is highly credible.”

(Fry 2024, 353)

I thank you for your attention and apologise for having taken so much time in anticipation of your Ithaca – the great Doctor Stephen Fry – but as Cavafy put it in his famous poem:

Σὰ βγεῖς στὸν πηγαιμὸ γιὰ τὴν Ἰθάκη, νὰ εὔχεσαι νἆναι μακρὺς ὁ δρόμος When you start on your way to Ithaca, pray that the journey be long. (Fry’s Odyssey incorporates the full poem in the Greek original and Avi Sharon’s 2008 English translation)

Further reading and exploring

Claes, Paul. 2024. “Παύλου Νικολάου Μοῦσαι: De Nieuw-Oudgriekse gedichten van Paul Claes.” Collected by Raf Van Rooy. Knowledge Commons. https://doi.org/10.17613/ecgf-aq87.

Fry, Stephen. 2024. Odyssey. London: Penguin Michael Joseph.

Lamers, Han. 2023. “A Homeric Epic for Frederick Henry of Orange: The Cultural Affordances of Ancient Greek in the Early Modern Low Countries.” Humanistica Lovaniensia 72:323–48. https://doi.org/10.2143/HLO.72.0.3292726

Lamers, Han, and Raf Van Rooy. 2022. “The Low Countries.” In The Hellenizing Muse: A European Anthology of Poetry in Ancient Greek from the Renaissance to the Present, edited by Filippomaria Pontani and Stefan Weise, 216–79. Trends in Classics – Pathways of Reception 6. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110652758-006

Murray, A. T., transl. 1946 [1919]. Homer. The Odyssey. 2 vols. London – Cambridge, MA: William Heinemann – Harvard University Press.

Van Rooy, Raf, Xander Feys, Maxime Maleux, and Andy Peetermans. DaLeT: Database of the Leuven Trilingue. www.dalet.be. Last accessed 18 December 2025.

The full slides of my introduction are available through this link.

How to cite?

Van Rooy, Raf. 2025. “Prelude to the interview with Doctor Stephen Fry (29 March 2025). The Odyssey in Leuven: Historical wanderings from Erasmus to Fry.” Adendros (blog). 18 December 2025. https://rafvanrooy.com/2025/12/18/doctorstephenfry/

Funding acknowledgments

Co-funded by the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) [project G040624N] and the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. The project ERASMOS (101116087) has received funding under the Horizon Europe programme.